tags:

Revelstoke, BC, Canada |

tgr news |splitboarding canada |splitboarding british columbia |splitboarding |splitboard mountaineer |splitboard guiding |splitboard guides in canada |splitboard guides |split personality column |split personality |rogers pass |professional splitboarders |joey vosburgh |how to become a splitboard guide |google news |genuine good gear |g3 |backcountry snowboarding

Sir Donald Basin, British Columbia. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Sir Donald Basin, British Columbia. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Joey Vosburgh, a professional backcountry snowboarder for G3 and Arc'teryx, is also one of Canada's most respected guides. He works for Selkirk Tangiers Heli Skiing as a heli guide, and for Whitecap Alpine and CAPOW as a splitboard guide. In between seasons, he checked in with us and described the long road to becoming a splitboard guide.

Can you detail the climbing, riding, and snowpack assessment skills one needs to be a guide in the backcountry?

Lickety Splitboarding Camp, Rogers Pass, British Columbia. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Lickety Splitboarding Camp, Rogers Pass, British Columbia. Joey Vosburgh photo.

I chose to take the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides (ACMG) stream of certification. In Canada, it's the one certification that certifies you in ski touring and mechanized skiing. It is a long, and challenging process, and I am proud to be an ACMG-certified Full Ski Guide.

I use the term "skiing" loosely as I completed the stream on my splitboard. In order to be accepted into the program you need a strong backcountry skiing resume, which includes multi-day backcountry ski trips, ski mountaineering summits, and travel through technical, glaciated terrain.

RELATED: Complete Guide To Improving Your Splitboard Transitions

You also need a bunch prerequisites. Being able to confidently, safely and efficiently travel in complex glaciated and alpine terrain is a must. In order to be able to do that safely, you need good snowpack assessment, map reading, and navigation skills. Really strong downhill abilities is essential, as is the ability to read and anticipate terrain so that you can manage what is coming up.

There is still a negative perception of how efficient splitboards are. It can be harder to deal with flats, for example. Certain terrain, if not identified, can magnify weaknesses of using a snowboard to guide on. So, have the years under your belt to recognize those weaknesses and know how to deal with them. You need to show that you can deal with the same terrain as a skier.

Can you talk about the various certifications that are required?

Vosburgh dropping in on Rogers Pass. Christina Lusti photo.

Vosburgh dropping in on Rogers Pass. Christina Lusti photo.

In order to be accepted into the programs, and then to continue working as a guide, you need a whole series of certifications. For the apprentice level courses, you need your Canadian Avalanche Association (CAA) Professional Level 1 course, and an 80-hour wilderness first aid course.

Once accepted into the program, the training courses start. There are three, and they are each about a week long. The first course is an alpine skills course. It outlines technical skills, such as rope work for glacial travel, short roping, and crevasse rescue. The second course is the mechanized training. You learn the operational side of guiding at mechanized operations, and the course focuses on “downhill guiding.” Third is the touring training. It outlines how to guide in a touring context, focusing on your “uphill” skills and traveling in technical alpine and glaciated terrain.

RELATED: Multigenerational sweat equity in the B.C. backcountry at Whitecap Alpine

This is where it starts feeling like an exam. You are either recommended to continue forward to the Apprentice Ski Exam, or you are urged to wait a year to gain more experience. The apprentice exam is eight days long, and it's pretty intense.

Once you are an Apprentice Ski Guide, you can guide only under direct supervision. Over the next couple of years, the supervision can become indirect and even remote. It's drilled into you pretty hard from the association that you are not a certified ski guide yet.

After a couple years of guiding, you need to do your Full Ski Exam, which is similar to the apprentice exam. The standards are higher, though. You are required to make high-end decisions with more flow, and very little or no coaching. The prerequisite for that is your CAA Level 2 course.

If you are successful with that exam, you go on to become the fully certified winter guide you have been chasing for so many years.

How did you go from skiing and riding in the backcountry to guiding? Can you talk about how you've developed as a professional, and what your goals are?

Eyeing a very steep entrance at Revelstoke. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Eyeing a very steep entrance at Revelstoke. Joey Vosburgh photo.

I started snowboarding when I was 12. Until I was 30, I had never thought about being a guide. Like many young shredders, I took chances and did a lot of foolish things in the mountains.

When I was 18, I took my CAA Level 1. My mom and I both realized that I would benefit from a bit of knowledge on snowpack and risk assessment. At that time, I was still limited by the snowshoes I was using. Starting to use splitboards made me more efficient and I was able to start really experiencing the backcountry.

In my late 20's, I moved from the Rockies in Alberta to Revelstoke, a place well-known for its heli skiing and ski touring. I fell in with a crew of highly motivated and experienced enthusiasts, many of whom were already guides. I watched Scott Newsome, an old friend from my Lake Louise days, battle his way through the ACMG. In time, he became the first snowboarder to pass the ski guide exams. It inspired me, and I began pursuing the same stream.

Over the years, I have worked really hard to hone my skills for guiding on my splitboard. Guiding has become my winter job, and I love my job. I never could have guessed how much I enjoy giving people a great day in the backcountry and seeing the stoke it brings people.

How has splitboard guiding progressed since its inception? What are some of the changes that you would still like to see happen?

What exam day looks like in Western Canada. Joey Vosburgh photo.

What exam day looks like in Western Canada. Joey Vosburgh photo.

My experience with becoming a ski guide was probably pretty different than Newsome's. Originally, for a snowboarder to pass the Ski Guide certification, they had to ski to pass the ski skills test.

Over the past five years, the ACMG accepted the splitboard as a tool. You can now go through the entire process on your splitboard. When you pass the exam, you are demonstrating that you meet the same standards as skiers, but on your splitboard.

Something I'd really like to see would be more operations supporting up-and-coming splitboard guides. I've been really lucky getting work from operations on my split, but I've heard of others running into road blocks.

Snowboard guides are still pretty new and some operations still seem hesitant to hire them. The reality is you need to have the skills on a snowboard to make whatever situation work–that may be quickly splitting and skiing a pitch or busting in a traverse to get your group to the goods. It really comes down to the individual and their abilities.

Can you talk about the people skills one needs in guiding, and how that plays into group dynamics and decision-making within a group setting?

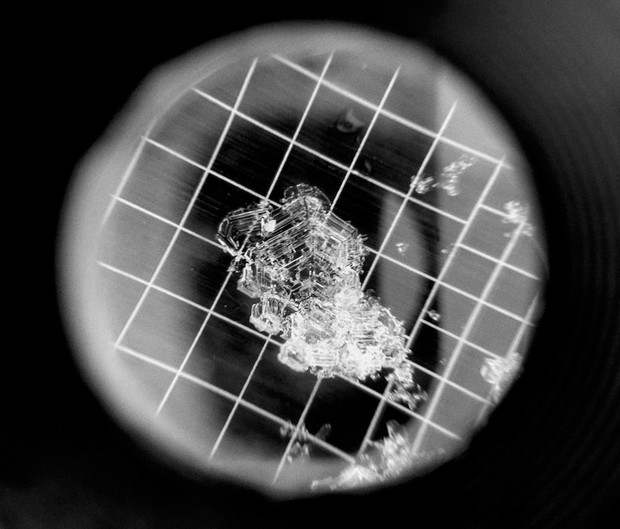

Surface Hoar. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Surface Hoar. Joey Vosburgh photo.

People skills are super important. They are a huge factor in how your day goes out there. It's like you need to be your client’s buddy and boss. You want everyone to have a good time, but you also need their respect in order to keep them safe. I try to be polite but not a pushover; to be optimistic but realistic.

In mechanized or large ski touring operations, your ability to work within a team is crucial. The daily guides' meeting at Selkirk Tangiers Heli-Skiing requires the team to work well together in order to get the most pertinent information from it.

I'm not always guiding with a team, so when I guide solo, I still try to communicate with other peers. It might be a phone call the night before to chat about changes in snowpack, or a quick coffee in the morning to go over weather and current conditions. The guides' meeting, whether at an operation or on your own, is super important to me. It's the first step in evaluating avalanche hazard and managing the risk before heading into the field.

Once out with the guests, it's important to listen to them not only verbally, but by observing the way they are moving in the snow. You may be able to adjust to different terrain to suit their needs or fitness levels, or give them verbal support and coaching in challenging terrain. Keeping all your guests stoked is key, but unfortunately, the backcountry isn't always bluebird and blower pow.

Can you walk us through a day in your life as a splitboard guide?

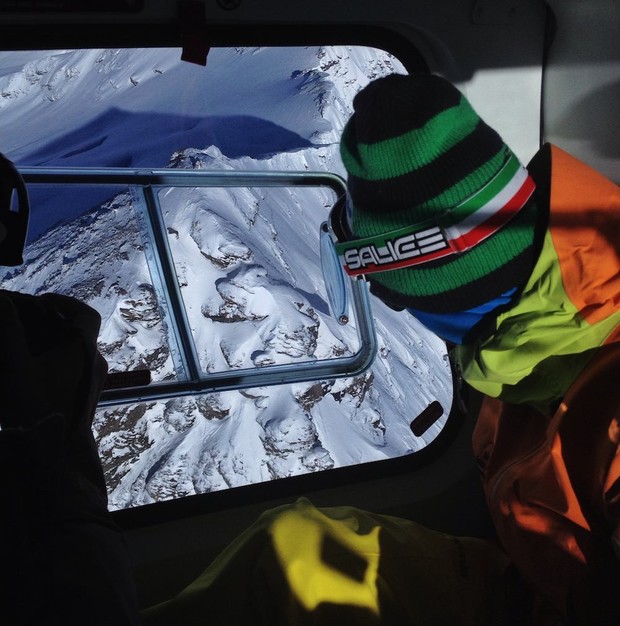

Scoping lines on La Grande Sassiere, France. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Scoping lines on La Grande Sassiere, France. Joey Vosburgh photo.

A day of guiding usually starts the day before, or maybe even days before. I try to keep my finger on the pulse of the weather and current avalanche problems. The night before, I fill out a bit of paperwork that document current conditions and avy problems, and I double-check the forecast.

The morning of, before meeting guests, I check the weather again and take note of overnight snowfall, wind and temps. I adjust my avalanche forecast from the night before. The decision of where to ride that day is based on numerous factors: my clients' ability level and fitness, current weather, snow conditions, avalanche hazard, and the weather forecast. Safe shredding is my highest priority. What is safe can change from day to day, so ultimately the mountains tell you where you can go.

Throughout the day, I am continuously monitoring how my clients are doing, what the weather is doing, and what the snow and avalanche conditions are. I adjust the day accordingly. The key is having a plan A, plan B, and probably a plan C. So whatever the day brings, you can have options.

What are some of the biggest challenges you face when it comes to risk mitigation and client expectations?

Skinning through a meadow in Whitecap, B.C. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Skinning through a meadow in Whitecap, B.C. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Managing guests' expectations can be one of the biggest challenges. It's common for guests to try and push you into bigger and more aggressive terrain.

Setting them up with realistic expectations is one of the first things I do. I fill them in on the type of terrain we can ski with respect to the current conditions. Sometimes it's deep pow in protected forests, and sometimes it’s big, steep alpine features. The goal is to take people to the best terrain given the daily conditions.

How you approach splitboard mountaineering missions in the backcountry and decide when someone is ready to hit a technical line? Once you've okayed them for that line, how do you go about prepping them, and guiding them through what's surely going to be a physical and mental challenge for them?

Joey in the Monashee Mountains. Joey Vosburgh photo.

Joey in the Monashee Mountains. Joey Vosburgh photo.

When I guide someone in big and technical terrain, I need to have complete trust in that person’s skills as a shredder and as a listener. I need to know they are capable of skiing the line and that they will follow my directions so that I can keep them safe. This trust is developed over days of guiding them. I won't take someone into big, gnarly terrain on the first day out with them.

Once I have a plan of where we will go, I'll give them a pretty detailed briefing outlining the day: how long will it take, what the weather will be, the cruxes and the highlights, as well as detailing the equipment they will need.

Some objectives will require an extra training session. For example, we might go through some crevasse rescue practice or teach them how to rappel. From there, it's just another day of guiding, coaching when needed, and giving positive reinforcement. The traveling pace can be adjusted throughout the day to best suit the guest fitness and ability.

__video_thumb.jpg)

__video_thumb.jpg)