This week in Women in the Ocean, we connected with activist and aspiring marine biologist Yassandra Marcela Barrios, who is fighting to protect her island's delicate coral reef. The Right to Roam photo.

This week in Women in the Ocean, we connected with activist and aspiring marine biologist Yassandra Marcela Barrios, who is fighting to protect her island's delicate coral reef. The Right to Roam photo.

There’s a whole hidden world along the coastline of Colombia’s Tierra Bomba Island. Underneath the crystal clear water lies a labyrinth of coral reefs, hosting a multitude of marine life: fish, anemones, sea lilies, and sponges all in colors brighter than most artists' palettes. The first time Yassandra Marcela Barrios saw this underwater ecosystem she instantly fell in love with its beauty. “I am an islander and my roots on Bocachica, surrounded by ocean, inspire me to love what surrounds me, especially the reef,” she writes to me in an email. As a local of Bocachica, a town nestled along the island’s shoreline, the reef has always been right in her backyard.

But it’s beauty, and vibrancy had long been unknown to her until the 19-year-old started diving with the Paraiso Dive Cartagena youth program. The initiative was spearheaded by divers and diving instructors Jose Uparela and Christina Kuntz to help educate local young islanders about reef conservation and diving. Barrios was one of their rare female pupils and has quickly become the most outspoken.

RELATED: Get to Know World Champ Carissa Moore in Her Film 'Riss'

Her time in the water has taught her one powerful truth: the livelihood of her community is intertwined with the reef. Right now, that reef is in peril.

The Right to Roam's film Dive Tierra Bomba Dive explores Barrios' quest to protect her island's coral reef.

Dive Tierra Bomba Dive from THE RIGHT TO ROAM on Vimeo.

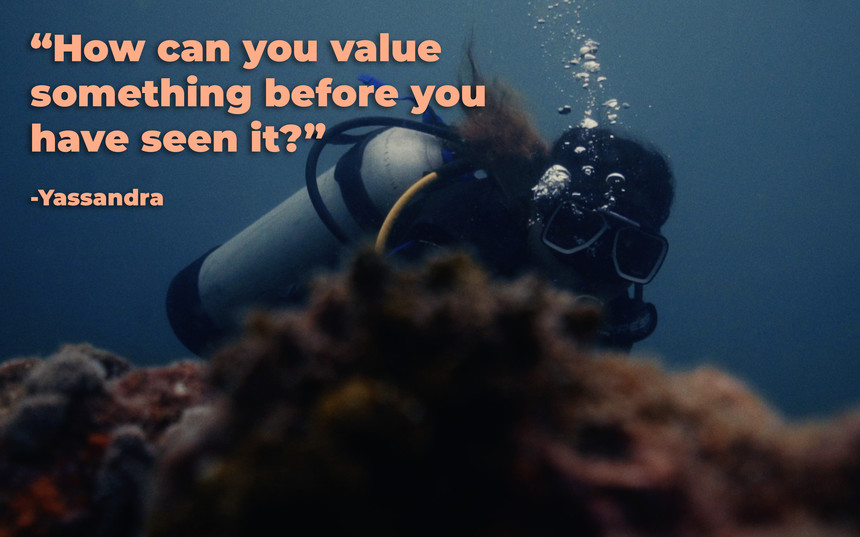

Whatever happens in this delicate marine ecosystem ultimately ripples back to Bocachica. These days, massive cargo ships crawl dangerously close to the shore, dumping chemicals and toxins into the water. The reef is showered with these pollutants, writhing some fragile coral in the process. No reef means no fish, and you don’t have to tell the fishermen here twice. Their empty nets and lines speak for themselves. Regardless, the families here need to eat something, forcing the community to take drastic measures like dynamite fishing. Not only does it further damage the reef in peril, but it’s risky. Some fishermen have even lost limbs in the process. Barrios watched this unfold around her with a heavy heart. She’s one of the lucky few who learned how to dive and the see reef firsthand, forcing her to grapple with this one question: How can you value something before you have seen it? For her, protecting the reef and her community starts with awareness.

It’s fairly common to find the spunky 19-year-old joining meetings with the local fishermen. Despite the overarching patriarchal attitude that Bocachica women ought to stay quiet and work in domestic roles, Castro sits on these meetings with poise. As the daughter of a fisherman, she’s been able to build a unique rapport with her fellow fishermen. She’s not afraid to explain how dynamite is damaging the coral, ultimately doing more harm than good.

Trust alone can’t solve her problems, which is why Barrios dreams of getting a degree in Marine Biology from the University of Cartagena on the nearby mainland. That’s easier said than done. Few women in her community seek higher education. Pregnancies are common at a young age, and most parents can’t afford tuition fees. “With an education in marine biology, I could do more. I could learn more about what I love and love so much, understand more about the species found in the sea. With this knowledge, I can help protect it.” Determined, she began a marine biology program at the university, requiring a two-hour boat commute each day. Right now, due to a variety of factors—COVID-19 being the biggest—Barrios’ studies have been put on hold. However, when her schooling resumes, Barrios still hopes to become the first marine biologist on her island. Equipped with this knowledge, she believes it will empower her to better advocate for the reef and educate her fellow islanders.

Yassandra regularly meets with the local fishermen to spread awareness about the coral reef. The Right to Roam photo.

Yassandra regularly meets with the local fishermen to spread awareness about the coral reef. The Right to Roam photo.

In the meantime, Barrios is finding other ways to teach her community about the reef. Last year she connected with the filmmaking duo Joya Berrow and Lucy Jane, who traveled out to Tierra Bomba to create a short film on Barrios. Their film company, The Right to Roam, focuses on telling stories that highlight underrepresented perspectives like Barrios who are fighting for environmental justice. Having lived in South America for nine months and seen devastated coral reefs firsthand, Berrow and Jane were intrigued and elated to hear about an outspoken teen trying to protect these delicate ecosystems.“She is still growing into this role as she is only 19. But she is a determined and intuitive role model. Yassandra is a climate activist, her voice is vital to the ocean conservation movement,” the filmmakers explained. “She shows how much positive impact one person can have, causing a ripple effect that could play a vital role in global conservation.”

During their stay on Tierra Bomba, they made a short edit of Barrios diving around the reef for her to use in one of her community presentations. By the end of the film, the whole room was interested in learning how to dive. For Barrios, that’s a major success in her book. If she wants to convince her community to change their habits, then she has to present a viable alternative. People are less willing to give up a lifestyle that leads to overfishing or dynamite blasting when they have a family to feed. Tourism, however, could bring sustainable work that Tierra Bomba needs.

Few tour guides and diving instructors are local on the Island, which is something that Paraiso Dive is striving to change. With its treasure trove of marine biodiversity and coral, Tierra Bomba especially has the potential to host divers and researchers from all over the world. “This would bring a new source income for us, and to have economic security for the future,” Barrios explains, meaning that her community could make a living from the reef rather than continue to exploit and destroy it.

Ultimately, positive change is necessary for the livelihood of islands like Tierra Bomba. They’ll be the first to feel the effects of coral reef degradation and climate change. Barrios’ story is a hopeful example of how Tierra Bomba and other marginalized communities can come together to protect not only their precious natural resources but imagine a better future for themselves.

__video_thumb.jpg)

__video_thumb.jpg)

__video_thumb.jpeg)

StevenG

August 5th, 2020

Good read, I did some house building work in Colombia a few years back (work with roofing and gutters san antonio now) so I always love to read about their people and the changes needed.

csjoshi9756

November 22nd, 2022

House Building Work FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022

FIFA World Cup 2022